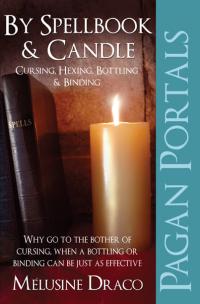

By Spellbook & Candle: Cursing, Hexing, Bottling and Binding

The subject of cursing is something that crops up quite frequently on social media, usually in the context of whether it’s ever justified. Plus the endless compendiums of superstition and folklore contain endless charms, talismans and amulets for protection against the witches’ curse. So, let’s put the subject into some form of perspective:

Curses have given the world its greatest stories, and the more grisly and gory, the better we like them. But cursing, or ill-wishing, is not confined to magical practitioners – black, white or

grey – it is a form of expression intended to do harm in reparation for some real or imagined insult. And can be ‘thrown’ by anyone of any race, culture or creed without any prior experience of ritual magic or witchcraft.

Curses have also been taken seriously in literature. In Phases in the Religion of Ancient Rome, we discover that Roman poets Ovid and Horace recorded all manner of cursing in their writings. Or the most famous (albeit apocryphal) – that of the last Grand Master of the Knights Templar, which inspired six dramatic novels by French author Maurice Druon – The Accursed Kings. Precious jewels connected to royalty and infamy have also inspired a variety of curses, especially where tragedy has repeatedly struck. As a result, the gems have been deemed to be cursed – with ruin and even death the unhappy lot of whoever owns them, as demonstrated in Simon Raven’s contemporary novel, The Roses of Picardie.

Folklore also casts long shadows, with some infamy bringing a curse down on a family, which in turn has resulted in numerous tall tales, like Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles, featuring fictional detective Sherlock Holmes. Elizabethan curses appear in Shakespeare … and the Bible, where the most vigorous and far-reaching are to be found in the

Old Testament … and in children’s stories such as Sleeping Beauty and Beauty and the Beast. And how many schoolgirls have giggled over Tennyson’s immortal lines: ‘The curse has come upon me,’ cried the Lady of Shallot?

Confusingly, some curses have passed into the language – the ‘Curse of Scotland’ for example can refer to (1) the nine of diamonds in the game of Pope Joan – the Pope, the Antichrist

of the Scottish reformers. (2) A great winning card in comette, introduced by Mary, Queen of Scots, and the curse of Scotland because it was the ruin of so many families. (3) The card on

which the ‘Butcher Duke’ wrote his cruel order after the Battle of Culloden. (4) Or the arms of Dalrymple, Earl of Stair, responsible for the massacre of Glencoe. (5) The nine of diamonds is said to imply royalty and ‘every ninth king of Scotland has been observed for many ages to be a tyrant and a curse to the country’. [Tour Thro’ Scotland, Grose 1789]

The dictionary definition is: To invoke or wish evil upon; to afflict; to damn; to excommunicate; evil invoked on another person, but under what circumstances can we challenge this established way of thinking and ask ourselves: Can cursing ever be justified? And if we hesitate for just a moment, then we must ask the next question: Is cursing evil? The Christian priesthood obviously felt their cause was just and as a result, the Church’s curses are so

virulent that it’s not just the ‘victim’ that suffers but their offspring in successive generations. And if a curse is thrown at the perpetrator of some terrible crime, can it really be deemed to be

evil?

One curse still heard quite regularly is: ‘A plague on both their houses!’ taken from Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. As John Wain observes in The Living World of Shakespeare, there is no reason, other than sheer stupidity and bloody-mindedness, that keeps the Montagues and Capulets at each other’s throats. The blame for the subsequent tragedy is equally divided between both families and therefore the curse should strike both in equal retribution, so is considered justified.

Nevertheless, do remember that curses, like chickens, have a habit of coming home to roost. This is because if not properly ‘earthed’, curses return to the curser, just as chickens that stray during the day return to their roost at night.

So … having ascertained that your ‘enemy’ is genuine, you must decide how you wish to repulse their advances. The form of your retaliation will be decided by your own personality and sense of morality – it is an extension of your own inner mind. There are no hard and fast rules, but do bear in mind that a half-hearted response is just as bad as going over the top. In either case you

will have misjudged or misread the situation; alerted your enemy to the fact that you’re on to them; and given them the opportunity to change tack. Take a look at your options:

• Double up on personal protection and take defensive measures rather than taking the war into the enemy’s camp;

• If you are not 100% sure of the source, channel the returning curse through your personal guardian/deity with the proviso that it should be ‘returned from whence it came’;

• If you are 100% sure of the source and you wish to pay back in kind, then the method, strength and outcome should be magnified three, five, ten or a hundred fold;

• If anger or ego is clouding your judgement, delay the return for 24 hours and reflect.

It is important not to be led astray by ego or paranoia because whatever anyone tells you, it is impossible to recall a curse once it’s been sent – which is why you need to be 100% sure of the source before retaliating. What you don’t want is to become embroiled in an astral equivalent of Gunfight at the OK Corral with magical six-guns blazing – it is tiring, time-consuming and

generates nothing but negative energy on both sides. Bob Clay-Egerton’s advice under such circumstances was: ‘There is nothing wrong with turning the other cheek, or with forgiving an offence. But there is nothing wrong either with taking protective measures against further slaps. If this is done, then you are perhaps doing a good deed by demonstrating to the attacker that, although you, yourself are not attacking, you are guarding yourself in such a way that their attacks are turned against themselves and that they are, in effect attacking, not you, but themselves. Beware then, not only of excess pride but also of excess humility. Both can be damaging.’

One of the most popular methods of deflecting a curse is to hang an empowered witch-ball in the main entrance hall of your home. The first written record of this method dates back to 1690 where a large glass ball, brightly painted to give a reflective surface to deflect any negative energies coming from any direction and returning them to the sender. A more modern application is the use of a mirrored ball that ‘confuses’ the energies with its broken or distorted patterns. The curse cannot connect and, having nowhere else to go, goes winging back to the sender, gathering momentum in the process.

Specifically vervain and dill were mentioned in the poem, Nymphidia, by Michael Drayton (c1627) – as a protective spell against curses. Accompany the installation of the ball with the sprinkling of those herbs cited in the 17th-century rhyme:

Trefoil, vervain, John’s wort, dill

That hindereth witches of the Will.

In Defences Against the Witches’ Craft, John Canard writes that he is a ‘great believer in returning the energy a person puts out to them. If they are sending you negative energy, reflect it to them and let them have a taste of their own medicine. The best way to ensure that somebody does not make the same mistake of directing negativity at you is to switch the tables so they receive what they were trying to give.’ But then … why go to the bother of cursing, when a bottling or binding can be just as effective?

So Mote It Be!

Pagan Portals: By Spellbook & Candle – Cursing, Hexing, Bottle and Binding by Melusine Draco is published by Moon Books. ISBN 978 1 78099 563 2 : Pages 90 : UK£4.99/US$9.95. Available in paperback or e-book format.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed